On a sad note, I have lost my camera. I did take a bunch of photos of the area, only a couple of the school and the class since honestly it was just a lot of talking and drawing. The below image is from the school website, just to show how nice the space is.

Over the weekend, I took a trip up to the Port Townsend School of Woodworking and Preservation Trades. In a word, it was fantastic. For more details, keep reading.

The trip (and I use that word in a few senses) unlocked an incredibly dense set of unfolding ideas, but I am able to roughly group them into 3 categories: the location, the school + staff, and the course material itself. I already wrote a bit about my impressions of the town, and my other bits of exploration only backed that up. It is an incredibly fertile location for artists, craftspeople, appreciators of nature, and outdoor athletes to find their happy place. I could wax poetic about Port Townsend, and the Pacific Northwest in general (including my current home in Oregon), but I will get to the more nuts-and-bolts ideas I had regarding the school and its classes.

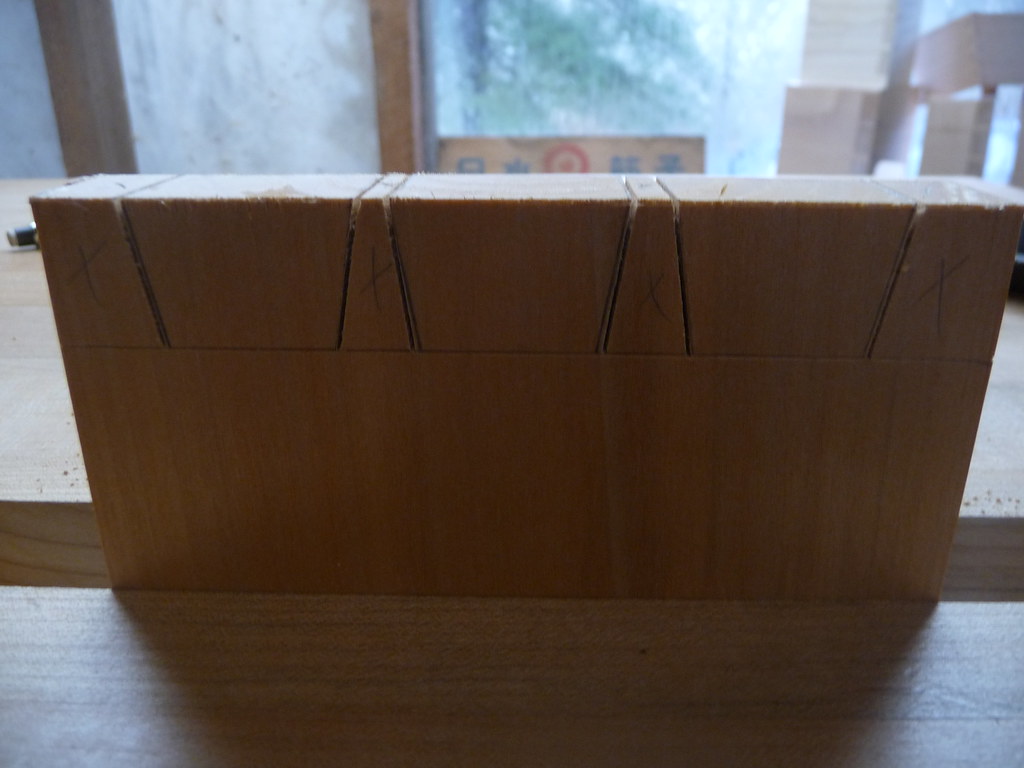

%201.jpg)

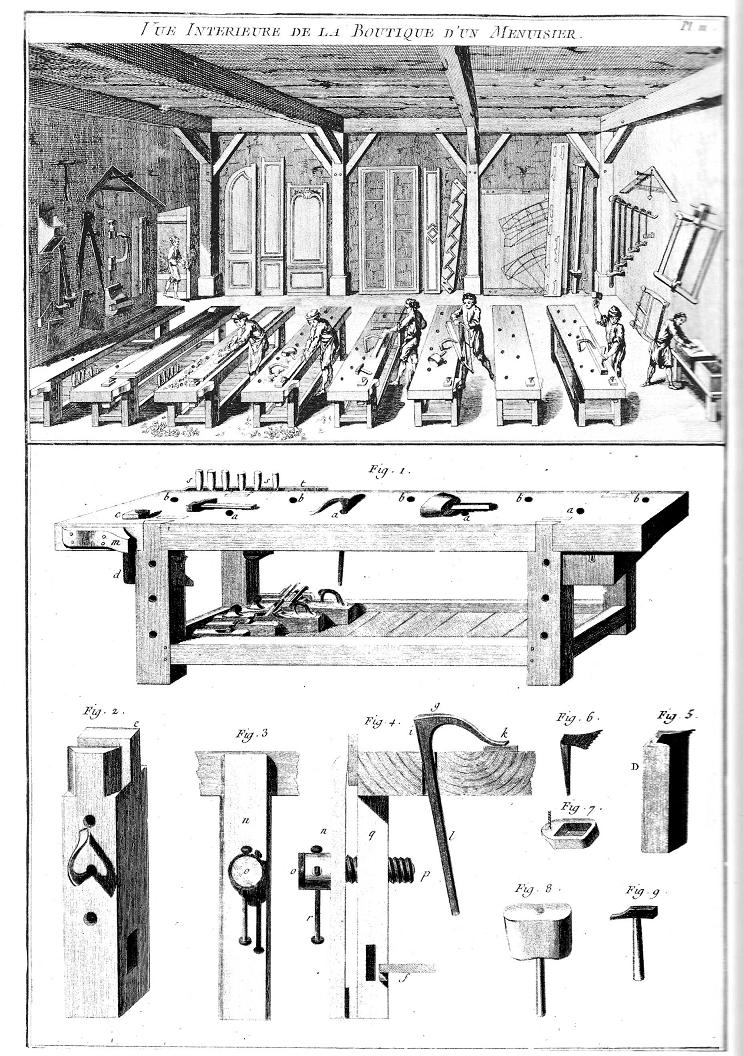

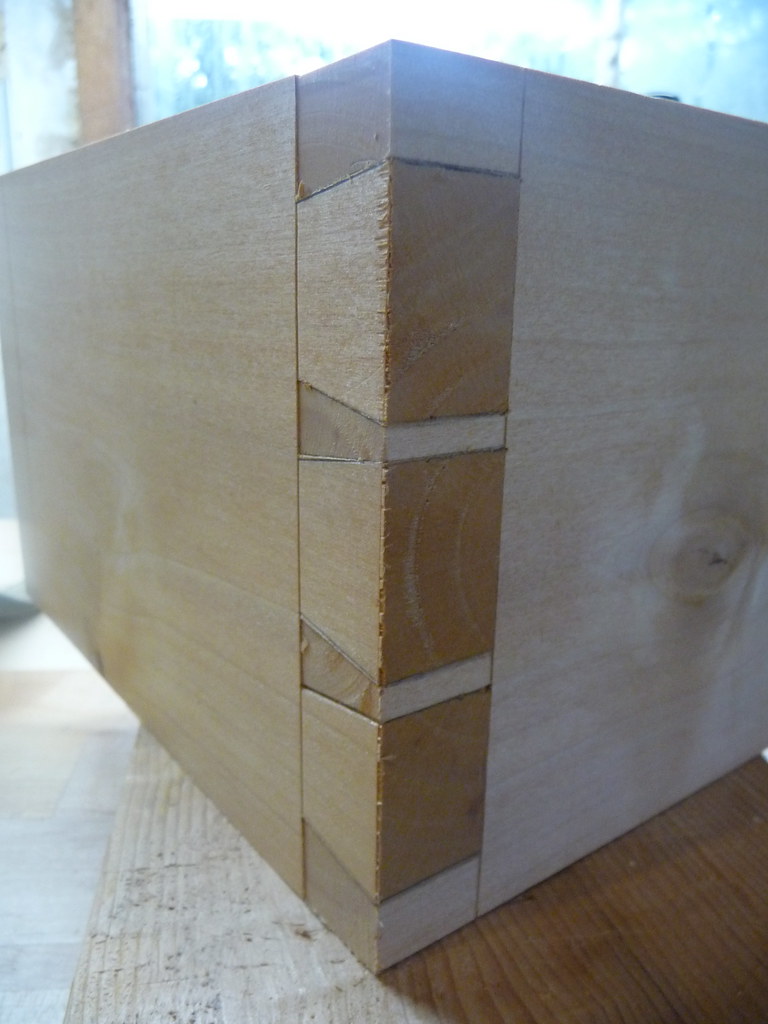

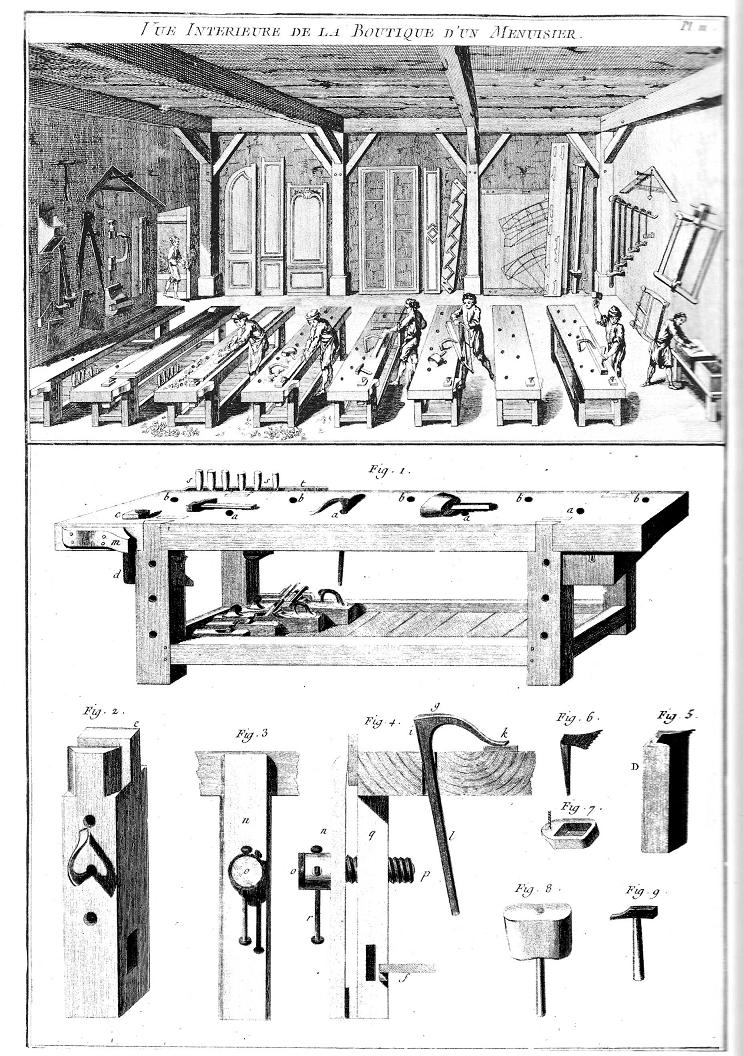

Just as I feel the town is an inspiring place to live, visit, or just be as a creator/appreciator of art and handiwork, so is the school a massive geyser of stimulating illumination regarding woodworking. The building itself is impressive; from the tools and benches themselves to its own infrastructure and features, it just has that kind of feng shui that can make woodworking feel enjoyable, or even mandatory. The very high ceilings provide an almost cathedral-like sense, reminding me of some of Roubo's shop images.

The space is clean, well-lit, and very well appointed. Every bench has a small storage unit beneath it stocked with essential tools of high quality. Marking and measuring, saws, chisels, block planes, and more are all right there for each student to have as their own for the duration of the course. The walls are then loaded with a lust-inducing array of saws, spokeshaves, planes (both bench and specialty) and more. The tools are all high-quality- a mix of vintage and new-, and expertly maintained by the staff so they are always sharp and ready to use. Sawbenches are also in abundant supply, and of various forms so that one may select a bench best fit to one's body size, or to perhaps aid in choosing a design if a bench needs to be built. Similarly, the spectrum of tools from different makers and eras allow one to try several varieties before deciding which they would most like to purchase.

Tools were not the only useful aids in learning to be had as part of the space, however. Since the building was created in an era which still utilized high degrees of craftsmanship, one can find lessons encoded in the windowsills, the stonework, and in the surrounding buildings. Another example was that while we were discussing how crown moulding angles up and into the room, lending an illusion of support to the ceiling, a sketch of a tree was provided on the white board. I immediately noticed that by looking out the window behind the instructor, a fat alder tree was perched right there, showing the exact phenomenon being described. This is quite a contrast from the last school I visited, which had not a single window. It was quite easy to imagine how enjoyable immersion in this school would be. I was the only student visiting for the first time; the rest were frequent fliers. I would, of course, like to join their ranks as regulars!

This brings us to the staff: very knowledgable, approachable, engaging, and charming, all of them. Tim Lawson, the executive director, was involved in much of the course. Take a look at some of Tim's amazing creations on his website,

http://timlawson.net/

Co-founder

Jim Tolpin, who's books I have long admired, was just as inspiring as I had expected, and perhaps moreso. He was deeply witty, wise, and in command of teaching skills that could make him a student's favorite professor. His ability to contextualize very abstract concepts was I dare-say mind-blowing, and that was quite important as this was a mostly theoretical class with almost no woodworking per se.

That would make this a good time to say a bit about the course itself. I do not want to go over all that much of the material, in part because I will not do it justice. I am still integrating it, and need to spend much time playing with the ideas we learned. I also would rather anyone interested in these ideas either take the course, or wait for Jim's upcoming book on the topics which I am burning to read. However, I will offer a few squirts of the essence of the course in order to try to convey exactly what the heck I am talking about.

Called "By Hand and By Eye", it was a jam-packed fractal idea-fest revolving around the notion that stupendously complex objects and structures have been made by humans for countless thousands of years without CAD, calculators, or even much arithmetic at all. The "By Hand" part has many meanings; a huge part of the school's focus is on hand-tool woodworking. While there is an impressive machine room, and much is done with these machines, there is certainly a hand-tool bias. As such, many of the concepts we explored were through the hand-tool lens. This is of course mandatory when studying antiques and old buildings. It carries a hint of another meaning, as well. The human body has long been one of the main measuring tools in construction. Buildings need to be sized to fit people; doorway dimensions, doorknob placement, height of steps and their railings, width of hallways, and on and on are all extrapolated from a typical human body (and yes, we did discuss what typical might mean, and the difficulties in one-size-fits-all solutions). Nonetheless, the hand is a core tool for carpenters when determining dimensions for an object:

"And he [Hiram] made a molten sea, ten cubits from the one rim to the other it was round all about, and...a line of thirty cubits did compass it round about....And it was a hand breadth thick...."

— First Kings, chapter 7, verses 23 and 26 (emphasis mine)

Another literal example of design being informed by a hand is that a credenza height is set to be where one can most comfortably set down and pick up a steaming pot of soup. By hand indeed!

The "By Eye" portion of the title refers to the idea that while there are scores of useful rules of thumb, none of them matter unless the results look good. Once acceptable structural integrity is achieved, and this is usually possible with a great range of sizes, angles, and sloppiness, the work is not a success if it doesn't look right. It is not difficult to train the eye, or the parts of the mind dealing with visual information, to detect parallel, plumb, straight, and true. It is also possible to start to notice specific ratios of length to width, such as knowing if a sign is 5:7 or 3:5 at a glance. It is also possible to become sensitive to ratios which don't please the eye, despite the structure being solid and square. Notice that window panes are generally a vertical rectangle. Horizontal rectangles are unpleasant. I suspect this is a mirror of the shape of the human body, which is nearly always taller than it is wide. A vertical window pane looks as if we can fly out of it, like a doorway, where a horizontal one looks like we would have to flatten ourselves like a rat to squeeze under it.

It was suggested that early constructions were often an attempt to build interface between man and the cosmos, and you can assign whatever floats your boat for cosmos. God, nature, the human-created artificial matrix, whatever. The fact rings true: when we build our surroundings (such as the room you are most likely in right now), and interact with the world outside our bodies (such as the chair you are probably sitting in), you are having your experience mediated by an object that was designed by a human. Hopefully, the room you are in and the chair you are on were designed by someone familiar with the concepts this class was about.

From there, we explored many of these rules of thumb, and ways to use them in our design of woodworking projects. We studied commonly pleasing ratios, and designed a table using them. Depending on the purpose of a table, it can often look quite nice when it its height is 2/3rds of its width, or similarly pleasant yet different at a 5:7 ratio. In general, whole-number ratios look good, and can look especially good when repeated throughout an object.

In traditional Western education, much was based on Greek studies, such as learning to identify and draft various types of columns. The poor students, and even instructors, were not wholly aware of why this was important. They were, without knowing about it, becoming familiar with proportional systems discovered, mapped, and encoded long, long ago. During the discussion about classical education, I actually became a bit angry that my modernized education was so light on traditional aesthetic studies. Of course, I would have wanted an instructor like Jim or Tim to explain why this stuff was important, but that gives me hope that these ideas can in fact be re-integrated into basic education. I know my daughter is going to grow up knowing a lot more about classical orders than I did!

The course touched on dozens or maybe even hundreds of "rabbit holes" which were tempting to spend an eternity travelling down, but the rather small class size made sure we all had time to bring up our own observations and interests, and could peer into these tunnels without being tortuously dragged down someone else's road. Several concepts for articles if not books were easy to pluck from some of the thinking out loud we all did.

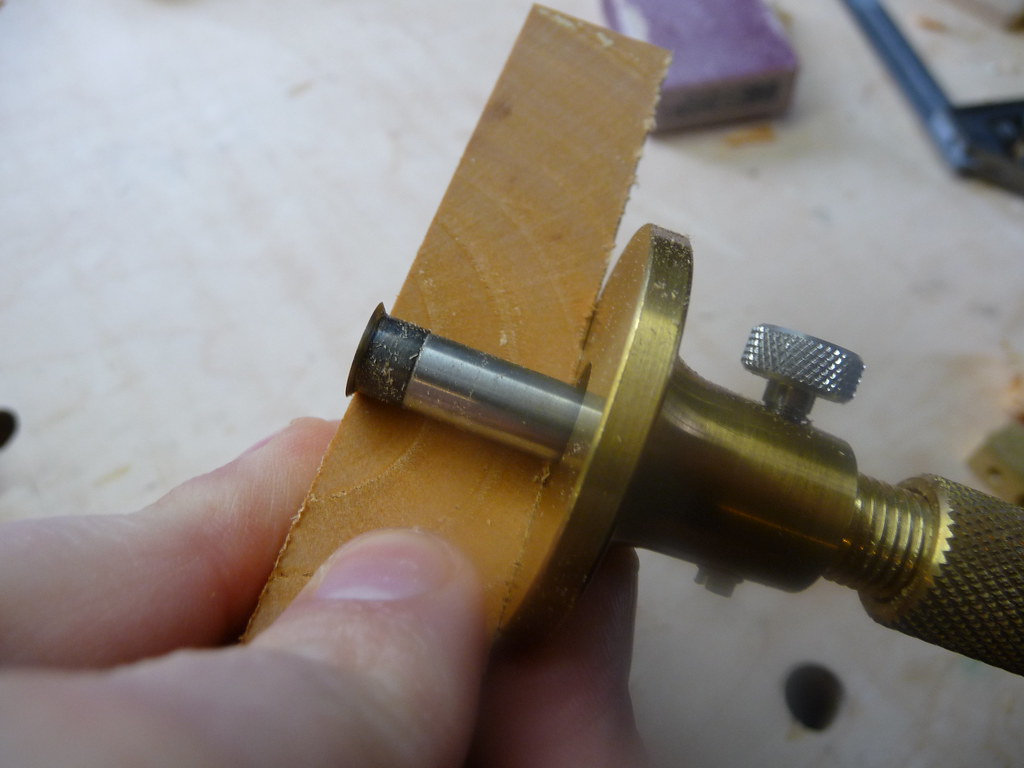

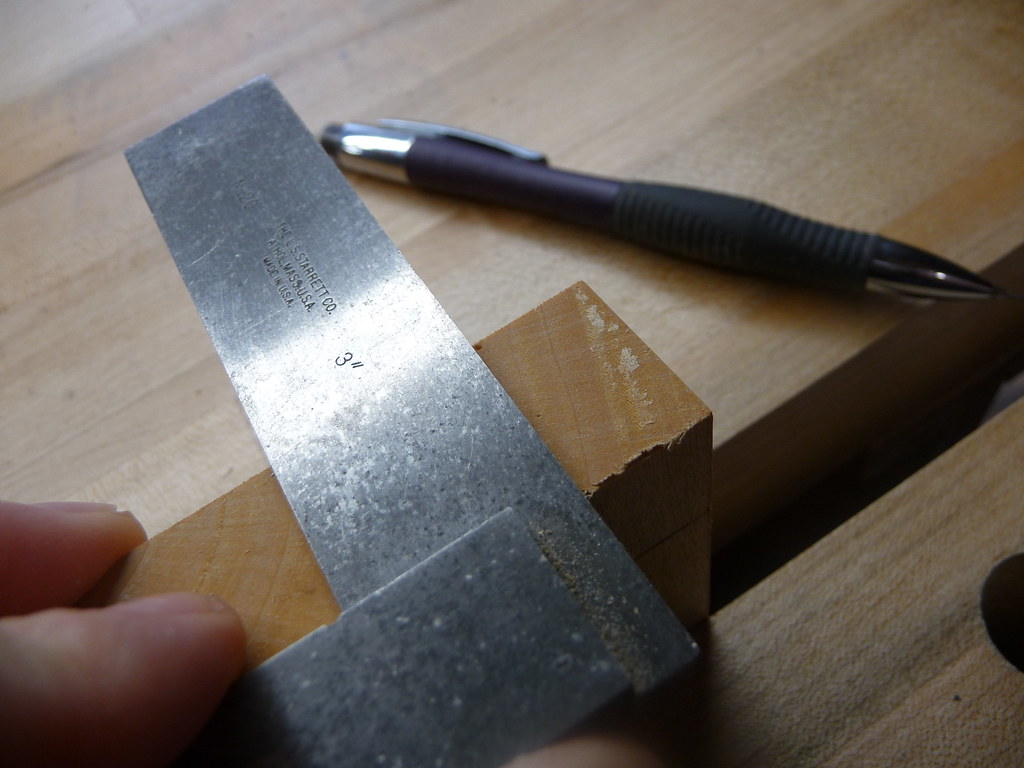

Our hands-on layout and design exercises were carried out using compasses, dividers, and straight edges. After warming up with some geometry exercises (again no arithmetic, just erecting right angles, plotting polygons and elipses, etc), we designed our tables, a chest of drawers with diminishing drawer dimensions, and then explored other design challenges as well as the methodologies used to generate ideas and then refine them. Group critiques of our designs were informative and fun. A couple of the proposed designs seemed like they actually might be built. Mine, however, were purely exercises although I feel way more confident in my ability to design a table or chest of drawers from absolute scratch instead of seeking out plans.

I would again implore anyone interested in these topics to attend the workshop, or at least read the upcoming book, but for those less interested, here are just a couple of the secrets we unlocked:

- The bottom rail of a door is usually a bit taller than the on on top. Why? How much taller?

- Drawer pulls are not vertically centered. Why not? How far off center should they be?

- Hanging cabinets will have different proportions than floor cabinets, but not for structural reasons. Why?

- How can the shape of very early aircraft be rapidly drafted with only a pair of dividers?

I could go on and on about this richly rewarding course, but there is no need for me to re-invent the wheel. I do want to mention that above I said we did "almost no" actual woodworking. We did each build a sector made of wood, which involved traditional marking and measuring operations, as well as a hint of planing and drilling. We were then taught to use this deceptively simple and amazingly powerful tool to determine proportions, adjust scale, and more.

As the group design critiques were useful, I would also like to critique this course, or the school in general, but honestly I would have to struggle to do so. It would be nice if the concrete floors of the shop were covered with wood, a very welcome change I did in my own shop. The benches all had pads, though, so I suffered no discomfort at all, and this is really reaching for a criticism. As for the course itself, it was all it advertised and more. Any miniscule troubles I had with it were due to my own issues (and I did undergo a bit of self-discovery throughout it) and were welcome if not expected components of the course. Lets just say that I enjoy being taken out of my comfort zones, being challenged, and having my mind blown open.

Many thanks to the school staff for creating this course and sharing it with us! I can't wait to get back.

%201.jpg)